|

|

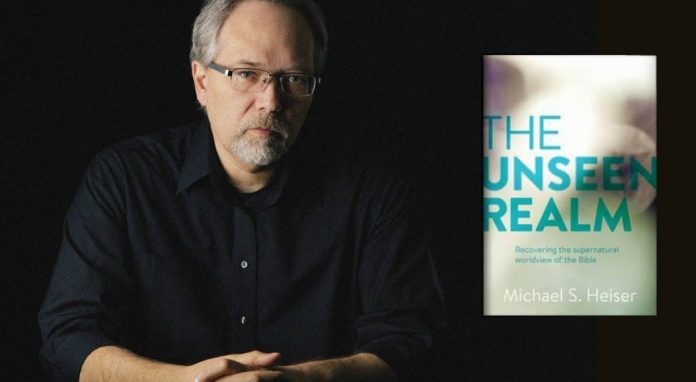

COMMENTARY ON AUTHOR MICHAEL HEISER

http://truthwatchers.com/michael-heisers-gnostic-heresy-of-a-divine-counsel-in-psalm-82-part1/

While working on a commentary for Psalm 1, I was planing to write an excursus on the how the phrase “counsel” and “sitteth in the seat” carry a concepual parallel to Psalm 82.

Being

aware of an “angelic” interpretation of Psalm 82, I planned to study

out the view to determine whether I could be persuaded that the “human

rulers” position was wrong. This turned my attention to Michael Heiser.

First, I read his doctorates dissertation on the topic which presented

a polytheistic view of the Bible. I was confused if what he was stating

was his actual opinion or if he was slanting it toward the liberal view

since his doctorates was from University of Madison which is a liberal

campus by secular standards. Next, I perused some of his scholarly

articles published in evangelical journals and was shocked to see the

same polytheistic opinion published by “conservative” evangelical

journals. I finally read his book The Unseen Realm which presents his

theological system as a whole which convinced me this man is teaching a

neo-Gnostic heresy which is being accepted by evangelicals.

In my book Crept In Unawares: Mysticism, I wrote in the preface about Peter Jones material in distinction to my own position. I stated, “The major difference between our works is that he primarily indicates that liberal theologians are working to revive Gnosticism, while I argue Gnosticism has already infiltrated that which may be considered conservative Christianity. The Bible predicts a growing apostasy in Christianity during the end-time, not unbelieving scholars reviving an ancient heresy.”1) Dr. Heiser fulfills this prediction in that his education is from the extreme liberal persuasion and his writings are targeting conservative evangelicals. However, after reading his Gnostic theological system as presented in his book The Unseen Realm, I was shocked to realize that the apostasy has grown to the degree that evangelicals would accept blatant Gnostic views. A glance at the footnotes of any of his writings will reveal his dependence on rank liberal scholars coming from publishing companies such as Brill and Tübingen.

Heiser’s Hermeneutic

The

root cause of the issue with Heiser’s theology is his interpretation

method, which errs on multiple levels. First, he interprets Scripture

in light of pagan literature to interject polytheism into the Bible. As

Peter Jones suggested of Gnosticism, “Whenever ‘Christian’ theology

looks to pagan polytheism for inspiration—as it is doing now and as it

did then—it discovers a titillating variety of reading techniques,

without which the Scriptures of the one, true God would be strictly

unusable.”2) Indeed, this hermeneutic method reigns supreme in Heiser’s

writings. One critic of Heiser has similarly commented, “Heiser has a

bad hermeneutical methodology because he has a bad hermeneutic

philosophy. This bad philosophy has led him to bad conclusions. There

have always been Christians who have tried to come up with some unique

and revolutionary interpretations. Heiser is not the first to come up

with this notion of a council of gods. You can see this in Gnosticism,

and Marcionism, and in other adaptations of basic Christian doctrines.

I’m sure he won’t be the last.”3) Heiser responded to Howe’s criticism,

stating, “I assume that the Scripture writers were communicating to

people intentionally – people that lived in their day and who shared

their same worldview. This assumption is in place because I’m sensitive

to imposing a foreign worldview on the writers.”4) In other

words, he admits his hermeneutics is focused on imposing the pagan

worldview on the Biblical authors, even though the Bible itself

commanded the Israelites to not enquire into the theology of their

pagan neighbors (Deuteronomy 12:29-32), and to destroy any Israelite

guilty of doing so (Deuteronomy 13:6-18). One simple example of this is

Heiser’s discussion of pagan deities were known to inhabit gardens and

mountains which he formulates an entire theology revolving around this

concept imported on the Bible.5) However, the Bible condemns this pagan

practice as idolatry on “high places” (Leviticus 26:30; Numbers 22:41;

33:52; Deuteronomy 12:2; 33:29; 1 Kings 3:2; 12:31-32; 13:32-33; 15:14;

22:43; 2 Kings 12:3; 14:4; 15:4, 33; 16:4; 17:11, 32; 21:3; 23:5; Psalm

78:58; Jeremiah 7:31; 19:5; 32:25; 48:35) and “groves” (Exodus 34:13;

Deuteronomy 7:5; 12:3; Judges 3:7; 1 Kings 14:15; 18:19; 2 Kings 18:4;

23:14; Isaiah 17:8; 27:9) with idols under “every green tree”

(Deuteronomy 12:2; 1 Kings 14:23; 2 Kings 16:4; 17:10; Isaiah 57:5;

Jeremiah 2:20; 3:6, 13: Ezekiel 6:13). God rebukes this idolatry that

Heiser thinks is valid biblical theology, “your iniquities, and the

iniquities of your fathers together, saith the Lord, which have burned

incense upon the mountains, and blasphemed me upon the hills” (Isaiah

65:7). Where is the logic of building a “biblical theology” by imposing

pagan practices which are specifically condemned in the Bible? One of

his foolish arguments for allegorizing his mountain opinion is

presented in his citing of Psalm 48:1-2, stating, “As anyone who has

been to Jerusalem knows, Mount Zion isn’t much of a mountain. It

certainly isn’t located in the geographical north—its actually in the

southern part of the country.”6) Mount Zion is on the north of the city

Zion, also called Jerusalem (2 Chronicles 5:2; Psalm 135:21; 147:12;

Isaiah 10:32; 30:19). He contends, “This description would be a

familiar one to Israel’s pagan neighbors, particularly at Ugarit. Its

actually out of their literature.”7)

Another

problem with Heiser’s hermeneutic is he focuses on ambiguous text,

plays fast and loose with the Hebrew language whenever he can, and when

he cannot twist an interpretation of the existing grammar to fit his

presupposition, he becomes the textual critic and changes the text

itself or uses a different text to justify his position. Other

Christian apologists have complained about Heiser’s handling of the

text. “Much of Dr. Heiser’s argument with respect to the text relies on

a higher critical framework that is repulsive to the traditional

evangelical scholar. This makes interacting with Dr. Heiser difficult

from the standpoint of finding any common ground upon which to premise

discussions.”8) Giovanni Filmoramo, a Italian Gnostic scholar indicated

the same issue with ancient Gnostics. “Gnostic editors manipulate the

sacred text in order to make it suit their purpose… by retouching,

adding a phrase or choosing a different translation.”9) In all this we

find that Heiser’s theology does not come from the Biblical text

itself, but is read into it from foreign pagan literature and when it

does not fit the grammar, he shifts the Biblical text to allow the

pagan worldview into the sacred scripture.

One

of the major rules of Biblical hermeneutics is to interpret the Bible

from passages that are clear and easy to understand, and do not

emphasize difficult passages; and definitely do not produce an entire

theological system based on a difficult passage. Norman Geisler and

Thomas Howe have written in their book When Critics Ask, concerning

these rules basic hermeneutic principles, errors are made when

“Neglecting to Interpret Difficult Passages in the Light of Clear

Ones.”10) They also reference the mistake of “Basing a Teaching on an

Obscure Passage.”11) Elaborating on this rule, they write,

'First, we should not build a doctrine on an obscure passage. The rule of thumb in Bible interpretation is “the main things are the plain things, and the plain things are the main things.” This is called the perspicuity (clearness) of Scripture. If something is important, it will be clearly taught in Scripture and probably in more than one place. Second, when a given passage is not clear, we should never conclude that it means something that is opposed to another plain teaching of Scripture.12)'

Heiser’s

theology is a perfect example of what happens when this fundamental

rule is ignored. He attempts to persuade his readers that “we have

layers of tradition that filter the Bible in our thinking.”13) But he

filters the Bible and his theology through ancient pagan Ugaritic

theology, not the Israelite religion as we all read in the Bible. He is

dependent on circular reasoning to find any nuance to confirm his

presupposition of this divine council. He states, “As with everything

else in biblical theology, what happens in the unseen world frames the

discussion [of eschatology].”14) So what frames everything in his

theology is what he calls “the Deuteronomy 32 worldview” which is

his filter to read the Bible through.

He frequently uses allegorical interpretations when the text cannot be interpreted toward his view. Heiser repeatedly uses the terms “symbolic interpretation” or “supernatural interpretation” to express his allegorical hermeneutics, similar to how Origen distinguished between the physical/literal versus the spiritual/allegorical methods. He states, “Literal readings are inadequate to convey the full theological message and the entirety of the worldview context.”15) Wrong! The literal interpretation is perfectly adequate unless you are attempting to force a foreign worldview into the text like Heiser is doing. He states, “Biblical writers regularly employ conceptual metaphors in their writings and thinking. Conceptual metaphor refers to the way we use a concrete term or idea to communicate abstract ideas. If we marry ourselves to the concrete (“literal”) meaning of words, we’re going to miss the point the writer was angling for in may cases.”16) There is a validity to this point, such as Christ calling Himself the “door” (John 10:7, 9); but this does not justify the extremes of Dr. Heiser.

Heiser

writes, “My task in this chapter and the next is to help you think

beyond the literalness of the serpent language. If it’s true that the

enemy in the garden was a supernatural being, then he wasn’t a

snake.”17) He then spends two chapter to explain why he needs to

allegorize away the literal interpretation. But why could it not be

both, a supernatural being possessing a snake. What could Genesis 3:14

possibly mean if not taken literally? Why did all the New Testament

authors express it in literal terms (2 Corinthians 11:3; 1

Thessalonians 3:5; Revelation 12:9)? Why did all the early translations

such as the Septuagint18) and the Peshita19) translate the word

literally as “serpent?” If allegorical interpretations are not enough

Heiser will revert to monkeying with the grammar. “But n–ch–sh are also

the consonants of a verb. If we changed the vowel to a verbal form

(recall that Hebrew originally had no vowels), we would have nochesh,

which means ‘the diviner.’”20) He also suggests nachash “copper, bronze

(by implication, shiney)”21) but says in a footnote, “I am not arguing

that nachash should not be translated ‘serpent.’”22) But that is

exactly what he is suggesting throughout the whole discussion, that the

word should not be understood as a literal serpent.

The

common claim of scholars that the Hebrew vowels did not exist in the

original is not established as fact, and history is strongly against

the slim evidence presented for such claims.23) The mere similarity of

consonants in the Hebrew language is no reason to suggest various

interpretations that would contradict the context of Genesis 3. “First,

the word nāhāsh is almost identical to the word for ‘bronze’ of

‘copper,’ Hebrew nehōshet (q.v.). Some scholars think the words are

related because of a common color of snakes (cf. our ‘copperheads’),

but others think that they are only coincidentally similar.”24)

Concerning the similarity of “serpent” and “divination,” Robert Alden

states, “some make a connection to snakecharming. More contend that

there is a similarity of hissing sounds between enchanters and serpents

and hence the similarity of words.”25) Of course, this similarity could

be just as coincidental, but there are word-plays on similar words in

Scriptures (Ecclesiastes 10:11; Jeremiah 8:17).

Heiser

does not limit his textual criticism to ignoring vowel points, but he

goes as far as altering consonants to completely change words in

conjunction with his “symbolic” interpretation to fit his agenda.

Speaking of Armageddon, he changes M-G-D to M-‘-D making it refer to

the “mountain of assembly” [har mo’ed] (Isa 14:13) and explains away

the final nun of the spelling in Zech 12:11.26) This is all based on

his idea that the battle takes place at Jerusalem not Megiddo, but the

text only says the armies are gathered to Megiddo (Rev 16:16) with no

mention of a battle waged in the area. Heiser alters the text which

reads מְגִדּוֹן and Ἁρμαγεδδών to read הַר-מוֹעֵד. He claims the Hebrew

consonant ayin (ע) make the sound of the letter g, but ayin is a silent

consonant. He is well aware of the fact that ayin and gimel are

significantly different and the use of these different Hebrew letters

reflect a humongous distinction. It would seem he is depending on his

readers to be ignorant of Hebrew.

This sets himself as the authority

for interpretation, making anyone not him unable to understand and thus

be dependent on his teachings. “The Hebrew Bible has many examples, but

they are obvious only to a readers of Hebrew who is informed by the

ancient worldview of the biblical writers.”27) Apparently that means

these “many examples” are only obvious to him since no one other than

himself is offering his bazar interpretations. I can read Hebrew and am

well acquainted with the ancient worldview of the surrounding pagan

nations of Israel, but nothing in Heiser’s theology is apparent to me.

To remark on his self-boasting, after reading over 1,000 pages of his

material, I have not seen him once referenced the most basic scholarly

text to be informed by the ancient world view popularly referred to as

ANET (Ancient Near Eastern Text Relating to the Old Testament).28)

He

is also very selective in what he is willing to recognize and

completely ignores the context that refute his presupposed theological

view. He admits he uses “a few selective points of connection and

issues relevant to those connection.”29) By ignoring the full counsel

of God’s word in order to select only what fits his presupposed pagan

worldview that he wants to force into the Scriptures, he has produced a

hybrid religious opinion just as the ancient Gnostic heretics. We will

assess particular points of where his major errors are in future

articles. To say the very least, Dr. Michael S. Heiser falls into the

category of what the apostle Paul meant when he wrote, “Now I beseech

you, brethren, mark them which cause divisions and offences contrary to

the doctrine which ye have learned; and avoid them.” (Romans 16:17)

Follow the entire series of assessing Hieser’s theology.

Michael

Heiser’s Gnostic Heresy (Part 1) is focused on Heiser’s hermeneutic

method as the root of his errors but is not very expressive of his

theology.

Michael Heiser’s Gnostic Heresy: Polytheism (Part 2) is

dealing with why he should be considered a polytheist even if he denies

the accusation. Simply put, his term “divine plurality” is what he uses

as a synonym to refer to his belief in many gods.

Michael Heiser’s

Gnostic Heresy: Redefining אלהים (Part 3) further elaborates his

polytheistic views and refutes his arguments against being labeled a

polytheist.

Michael Heiser’s Gnostic Heresy: gods or Angels (Part 4)

discusses how other Bible scholars that have similar research in Second

Temple Jewish literature understand this language to refer to angels,

not gods.

Michael

Heiser’s Gnostic Heresy: Deification (Part 5) may be the most

significant assessment of Heiser’s theology and draws on the many

parallels of his theological views and Gnosticism and exposes his

heretical doctrine that men become gods.

Michael

Heiser’s Gnostic Heresy: Paradigm passages (Part 6) [not yet available]

will discuss Heiser’s paradigmatic passages to explain his errors and

provide an accurate exegesis of Psalm 82; Deuteronomy 4:19-20; 32:8-9;

and John 10:34.